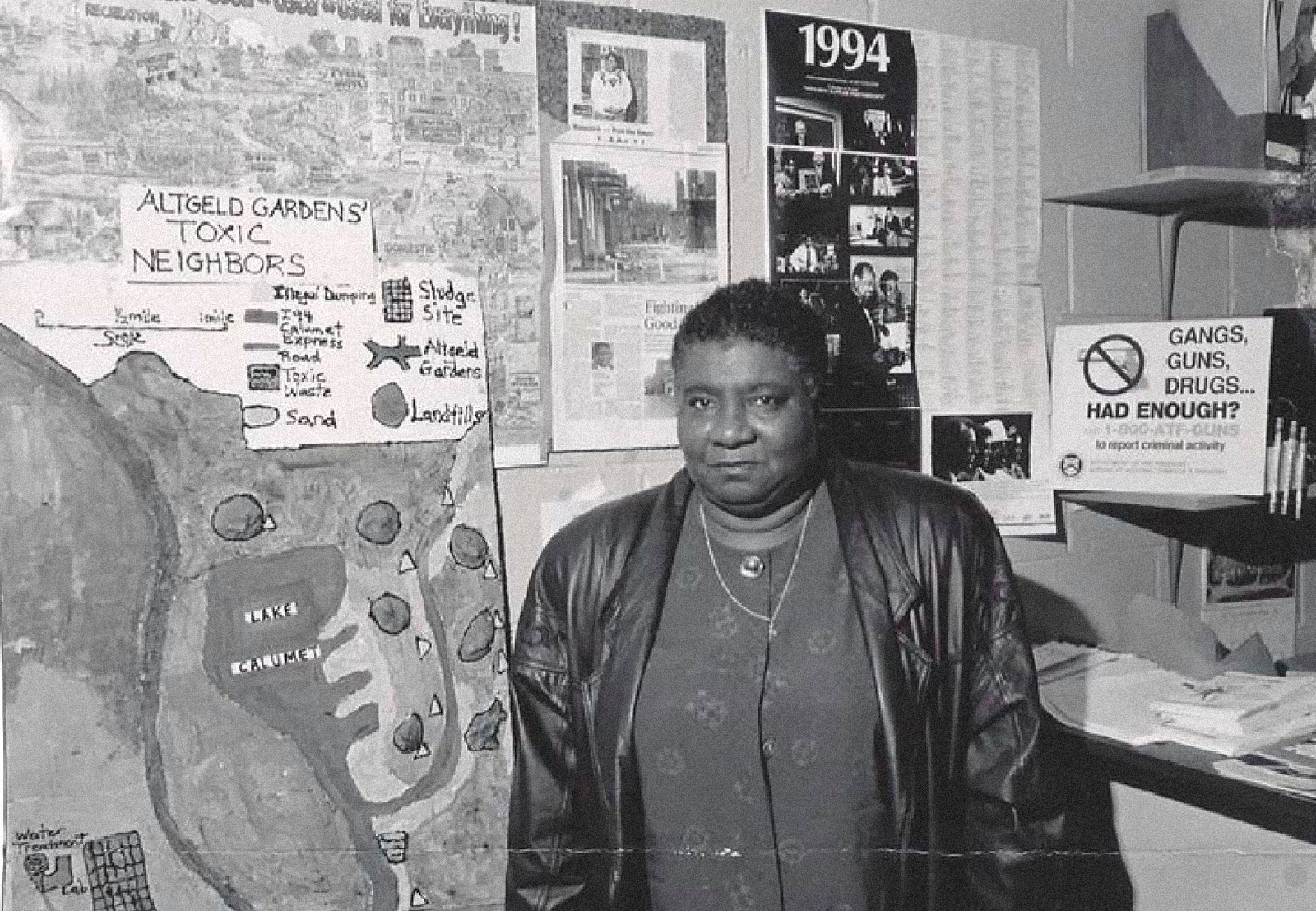

In 1969, about a decade after Hazel M. Johnson and her family moved from New Orleans to the Southeast Side of Chicago, her husband died of lung cancer. Around the same time, each of her seven children began experiencing skin irritation, respiratory issues like asthma, and fainting spells. The culprit, Johnson determined after exploring her new neighborhood, was what she called the “toxic donut,” a ring of landfills, sewage treatment plants, steel mills, and chemical factories surrounding Altgeld Gardens, the public housing complex in which the family lived.

Ten years later, Johnson founded People for Community Recovery, or PCR, to advocate for simple repairs and beautification in Altgeld Gardens. But after learning of the cancer deaths of four of her infant neighbors on the news, she began contacting government health boards, regulatory bodies, academics, and activists to try to make broader environmental changes to the neighborhood. She knew she had to expand her organization’s mission to fight the environmental racism she saw plaguing her majority-Black community — and that’s exactly what she did for the next three decades.

Now, 10 years after Johnson’s death in 2011, the U.S. may soon celebrate April as Hazel M. Johnson Environmental Justice Month. Bobby Rush, a Democrat representing Johnson’s Southeast Side community in Congress, has introduced legislation that would make the designation official. Rush’s legislation would also posthumously award Johnson, known in many quarters as the “mother of environmental justice,” the Congressional Gold Medal and her own postage stamp.*

Johnson’s daughter, Cheryl, who has been leading PCR for the past decade, wishes her mom had lived to witness environmental justice enter the national mainstream.

“I wish my mother was here to see it,” she told Grist. “She was one of the many trailblazers for environmental advocacy, and I know she would be pleased to see Biden’s administration taking it to the level it’s supposed to be.”

Hazel Johnson spent her life fighting for Chicago’s Southeast Side. When she first started organizing in the 1970s, she quickly found that her work would be cut out for her. The Southeast Side had the highest incidence of cancer in the city. Johnson’s 190-acre housing tract was surrounded by roughly 50 documented landfills and nearly 300 underground chemical storage tanks leaking cancerous compounds like liquid silicon tetrachloride. The area’s running water was known to be contaminated with nitrogen, phosphorus, and pathogens well above Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, limits. Nearby industries were (and still are) regularly cited for spewing unhealthy amounts of diesel pollution and particulate matter into the air. In her housing complex, Johnson organized to fix lead pipes and remove asbestos, which regularly hospitalized young children.

“My mother wasn’t trained or educated in the environmental sciences,” her daughter said. “But it was her mother wit that gave her the strength to challenge these injustices to protect children and families in our community.”

Since the 1980s, Johnson’s organization has been responsible for several environmental victories, including lobbying for EPA money for new water and sewage lines, getting companies to clean up their decommissioned projects, and training local residents to become environmental remediation workers. This work led to Johnson being honored with an award from then-President George H.W. Bush; she also helped inspire subsequent President Bill Clinton’s signing of the first-ever executive order on environmental justice.

Johnson’s life and work are a testament to the power of community and a model for future generations, according to her daughter.

“Honoring my mother now is not only about honoring the work she did, but showing us what our future can look like,” she said. “One of the things my mother showed people is that we know how to ‘dirty up’ in this country, but we don’t know how to clean up.”

Today, under Cheryl’s leadership, PCR has continued the work of environmental remediation and advocated for the cleanup of the decades-old sites of environmental harm. It’s also at work blocking new sites, like a controversial scrapyard set to be located on the Southeast Side after closing down in a whiter and wealthier part of town. The scrapyard, which Cheryl calls a “classic example of environmental racism,” has spurred large-scale protests, multiple federal lawsuits, and an intervention by EPA administrator Michael Regan, but it may still open for business in the coming months.

“This is why my mother named our community ‘the toxic donut,’” Cheryl said. “Since 1852, our community has been the dumping ground for Illinois. This has to change.”

While the fight for environmental justice was lonely when Hazel Johnson first began her activism, her daughter says she knows her mother would be proud to see how her work has grown and transformed.

“What makes the movement so powerful today is that our young people get it and have taken her words and fight to a new level,” Cheryl told Grist. “My mother taught us that environmental justice is like an umbrella, and the spokes within the umbrella are made up of things like housing and economic justice, health, and education. If the spokes are broken, then the umbrella is inoperable. Young people today see that and are making the connections of environmental justice to civil rights and the Black Lives Matter movement.”

Cheryl knows the fight for environmental justice in her community and across the country is a lifelong struggle, but recognition for her mother would be a reminder of how far things have come.

“I hate to sound like it’s about bragging rights, but how great would it be to see my mama on a postage [stamp]?” she said with a chuckle. “And then the added awareness for our future generations and our environmental issues — what an awesome opportunity.”

*Correction: This story originally misstated the name of the Congressional award for which Hazel M. Johnson was posthumously nominated.